Apartheid Reincarnated?

February 05, 2016

By James N. Kariuki*

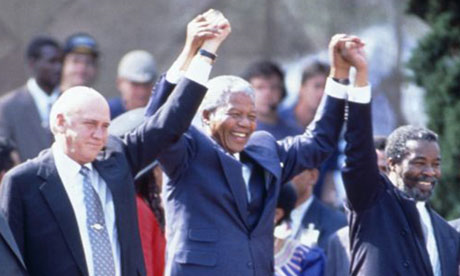

[caption id="attachment_26012" align="alignleft" width="460"] Nelson Mandela at his presidential inauguration with his deputies, FW de Klerk and Thabo Mbeki. Photograph: Photoshot[/caption]

A year ago, South Africans welcomed 2015 but were quickly repelled by its agonizing reminders of apartheid. On January 30, 2015 Eugene de Kock was granted parole after serving over twenty years in prison. His freedom sparked an agitated national debate on the apartheid regime’s crimes generally and those of de Kock particularly. It was an alarming déjà-vous experience.

De Kock was a self-confessed killing-machine that assassinated hundreds of anti-apartheid activists in the 1980s and early 1990s. Nicknamed ‘Prime Evil’ for his excesses, he was sentenced to two life terms plus 212 years in prison for six apolitical murders and other brutal acts as the head of the infamous official hit-squad near Pretoria. Yet, upon conviction de Kock launched a spirited campaign for his freedom. After two decades as a model prisoner, he was indeed set free, destiny unrevealed.

‘Prime Evil’ objected to his incarceration because he allegedly was singled out as a scapegoat; he did not act alone in the political carnage of apartheid’s sunset years. Indeed, he further alleged, the highest political office in the land was involved in what was mislabeled as black-on-black violence of the era. Yet, de Kock lamented, apartheid’s top brass walked unscathed. To him, that was ‘selective justice’; universality of justice was compromised.

De Kock’s release occasioned a public outcry that, for the life of each of his victims, he spent barely minutes in prison. Did that punishment match the crimes? Did de Kock’s freedom depreciate the lives of his black victims who paid the ultimate price?

Concurrently, in January 2015 South Africa was locked in another racially-tinged debate: should Cape Town re-name one of its major streets after F.W. de Klerk? Two days before de Kock’s parole was announced, Mother City actually renamed its Table Mountain Boulevard after de Klerk despite audible public objections. Cape Town’s obliviousness to loud objections was spiteful and reminiscent of the objectors’ painful apartheid days. Why so?

F.W. de Klerk was the last of apartheid’s seven presidents. He was a product of that political order and prominent enough to have served in several of its cabinet positions. When de Kock claimed that the top brass of the apartheid’s regime was guilty of political killings of the early 1990s, de Klerk topped his list.

By the end of January 2015, South Africa was thus bedeviled by two contrasting apartheid legacies. To Kock, a confessed mass murderer, was ultimately set free which prompted a public outcry. But in his case there was a mitigating factor: he regretted his crimes. Still, the price he paid was minuscule compared to the plight of his fallen struggle victims and their bereaved families.

Meanwhile, de Klerk was spared of criminal scrutiny for his ‘alleged’ sins. In fact January 2015 saw him elevated to a towering historical figure by re-naming a major Cape Town street after him.

Did the virtually uncontested freedom for a confessed and an alleged apartheid ‘murderer' denigrate the sacrifices of the Black anti-apartheid martyrs?

De Klerk’s culpability slipped legal scrutiny partly because he had entrenched himself as a convincing link between the principal contestants in the bid to dismantle apartheid. After all, he was astute enough to accept apartheid’s inevitable doom and bold enough to attempt to shape the incoming order. Conversely, Nelson Mandela’s leadership craved to see apartheid’s quick demolition and the birth of a rainbow nation of equals. Hence, its devotion to racial reconciliation.

Under these inspirational circumstances, De Klerk became an indispensable asset in the quest for a better South Africa. He had the ear of both the tenacious liberation movements and the skeptical Afrikaner community. His freedom and safety were non-negotiable; they were in the national interest. But still, did de Klerk walk away with murder?

SA did negotiate a peaceful transition to constitutional democracy. Well-wishers and genuinely interested parties, Norwegian Nobel Peace Prize Committee included, were convinced that the feat was worthy of awarding the 1993 Peace Prize jointly to de Klerk and Nelson Mandela.

But skeptics doubted that the SA president was worthy of the honor. After all, de Klerk never condemned apartheid morally, or expressed regrets that the evil system ever existed. His sadness was merely that, when it faced considerable stress, apartheid wilted became dysfunctional.

To his detractors, de Klerk’s stance was flawed for lacking moral conviction. To this day, he continues to defend aspects of apartheid despite its universal condemnation as a crime against humanity.

Stubborn questions still endure: to cross the line from apartheid to the negotiations table, did de Klerk jump or was he pushed over the cliff? Was the thrust to dismantle apartheid derived from a moral impulse or from seeing a window of opportunity to obliterate an already dying order? Was the collapse of apartheid fuelled by a ‘discovery’ of its injustice or from de Klerk’s acute instinct for survival?

By failing to discredit apartheid morally, de Klerk fell short of Abraham Lincoln’s stature of a compelling historical crusader who led a bitter civil war against American slavery because it was intrinsically wrong. De Klerk remained a crafty tactician and a bona fide believer in apartheid to the bitter end. He only abandoned apartheid to the old slogan, “If you cannot beat them, join them.”

As a political schemer, de Klerk was not deserving of the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize. To countless Black South Africans he was their oppressor not their liberator. He did not merit having a Cape Town street named after him either.

In January 2015, the city of Cape Town was mindful of the Black community’s skepticism about de Klerk’s role in their history. Yet it proceeded, with an air of bravado, to exalt him to higher prominence by renaming its street in his honor, not because it was politically fitting, but just because it could.

Was this apartheid under another guise? If not, it certainly smacked of what has been dubbed “transmission of trauma and humiliation from one generation to the next” for a large segment of the society.

*James N. Kariuki is a Kenyan Professor of International Relations (Emeritus), now an independent writer based in South Africa. He runs the blog Global Africa

Nelson Mandela at his presidential inauguration with his deputies, FW de Klerk and Thabo Mbeki. Photograph: Photoshot[/caption]

A year ago, South Africans welcomed 2015 but were quickly repelled by its agonizing reminders of apartheid. On January 30, 2015 Eugene de Kock was granted parole after serving over twenty years in prison. His freedom sparked an agitated national debate on the apartheid regime’s crimes generally and those of de Kock particularly. It was an alarming déjà-vous experience.

De Kock was a self-confessed killing-machine that assassinated hundreds of anti-apartheid activists in the 1980s and early 1990s. Nicknamed ‘Prime Evil’ for his excesses, he was sentenced to two life terms plus 212 years in prison for six apolitical murders and other brutal acts as the head of the infamous official hit-squad near Pretoria. Yet, upon conviction de Kock launched a spirited campaign for his freedom. After two decades as a model prisoner, he was indeed set free, destiny unrevealed.

‘Prime Evil’ objected to his incarceration because he allegedly was singled out as a scapegoat; he did not act alone in the political carnage of apartheid’s sunset years. Indeed, he further alleged, the highest political office in the land was involved in what was mislabeled as black-on-black violence of the era. Yet, de Kock lamented, apartheid’s top brass walked unscathed. To him, that was ‘selective justice’; universality of justice was compromised.

De Kock’s release occasioned a public outcry that, for the life of each of his victims, he spent barely minutes in prison. Did that punishment match the crimes? Did de Kock’s freedom depreciate the lives of his black victims who paid the ultimate price?

Concurrently, in January 2015 South Africa was locked in another racially-tinged debate: should Cape Town re-name one of its major streets after F.W. de Klerk? Two days before de Kock’s parole was announced, Mother City actually renamed its Table Mountain Boulevard after de Klerk despite audible public objections. Cape Town’s obliviousness to loud objections was spiteful and reminiscent of the objectors’ painful apartheid days. Why so?

F.W. de Klerk was the last of apartheid’s seven presidents. He was a product of that political order and prominent enough to have served in several of its cabinet positions. When de Kock claimed that the top brass of the apartheid’s regime was guilty of political killings of the early 1990s, de Klerk topped his list.

By the end of January 2015, South Africa was thus bedeviled by two contrasting apartheid legacies. To Kock, a confessed mass murderer, was ultimately set free which prompted a public outcry. But in his case there was a mitigating factor: he regretted his crimes. Still, the price he paid was minuscule compared to the plight of his fallen struggle victims and their bereaved families.

Meanwhile, de Klerk was spared of criminal scrutiny for his ‘alleged’ sins. In fact January 2015 saw him elevated to a towering historical figure by re-naming a major Cape Town street after him.

Did the virtually uncontested freedom for a confessed and an alleged apartheid ‘murderer' denigrate the sacrifices of the Black anti-apartheid martyrs?

De Klerk’s culpability slipped legal scrutiny partly because he had entrenched himself as a convincing link between the principal contestants in the bid to dismantle apartheid. After all, he was astute enough to accept apartheid’s inevitable doom and bold enough to attempt to shape the incoming order. Conversely, Nelson Mandela’s leadership craved to see apartheid’s quick demolition and the birth of a rainbow nation of equals. Hence, its devotion to racial reconciliation.

Under these inspirational circumstances, De Klerk became an indispensable asset in the quest for a better South Africa. He had the ear of both the tenacious liberation movements and the skeptical Afrikaner community. His freedom and safety were non-negotiable; they were in the national interest. But still, did de Klerk walk away with murder?

SA did negotiate a peaceful transition to constitutional democracy. Well-wishers and genuinely interested parties, Norwegian Nobel Peace Prize Committee included, were convinced that the feat was worthy of awarding the 1993 Peace Prize jointly to de Klerk and Nelson Mandela.

But skeptics doubted that the SA president was worthy of the honor. After all, de Klerk never condemned apartheid morally, or expressed regrets that the evil system ever existed. His sadness was merely that, when it faced considerable stress, apartheid wilted became dysfunctional.

To his detractors, de Klerk’s stance was flawed for lacking moral conviction. To this day, he continues to defend aspects of apartheid despite its universal condemnation as a crime against humanity.

Stubborn questions still endure: to cross the line from apartheid to the negotiations table, did de Klerk jump or was he pushed over the cliff? Was the thrust to dismantle apartheid derived from a moral impulse or from seeing a window of opportunity to obliterate an already dying order? Was the collapse of apartheid fuelled by a ‘discovery’ of its injustice or from de Klerk’s acute instinct for survival?

By failing to discredit apartheid morally, de Klerk fell short of Abraham Lincoln’s stature of a compelling historical crusader who led a bitter civil war against American slavery because it was intrinsically wrong. De Klerk remained a crafty tactician and a bona fide believer in apartheid to the bitter end. He only abandoned apartheid to the old slogan, “If you cannot beat them, join them.”

As a political schemer, de Klerk was not deserving of the 1993 Nobel Peace Prize. To countless Black South Africans he was their oppressor not their liberator. He did not merit having a Cape Town street named after him either.

In January 2015, the city of Cape Town was mindful of the Black community’s skepticism about de Klerk’s role in their history. Yet it proceeded, with an air of bravado, to exalt him to higher prominence by renaming its street in his honor, not because it was politically fitting, but just because it could.

Was this apartheid under another guise? If not, it certainly smacked of what has been dubbed “transmission of trauma and humiliation from one generation to the next” for a large segment of the society.

*James N. Kariuki is a Kenyan Professor of International Relations (Emeritus), now an independent writer based in South Africa. He runs the blog Global Africa