Brazil-Africa: Trans-Atlantic ties

June 21, 2014

Brasília Teimosa, an oceanfront settlement in the north-eastern city of Recife, is gentrifying. Rents are rising, and homes are taking on new floors and replacing their weather-beaten facades with gleaming ceramic tiles studded with aluminium doors and windows. Hotel porter Romualdo Andrade, 45, points out a series of steel street lights being installed to replace the concrete ones. They are more resistant to the salt-strewn breeze from the shark-infested ocean, he explains. "The only thing that resists the salt breeze is ugly girls," Andrade says, laughing.

He traces the turning point to about a decade ago, when President Luiz Inácio 'Lula' da Silva spearheaded a four-part regeneration project that involved pulling down the least habitable of the settlement's structures – while paying the occupants a monthly allowance to enable them to rent proper housing – and building a sea wall, roads and parks.

About five decades ago, Brasília Teimosa was a proper slum full of houses on stilts that rose out of the swamp. The Teimosa in its name means stubborn, Andrade says – a testament to the resistance its earliest inhabitants put up in the face of government attempts to demolish the slum and pave way for the reassignment of the prized land to developers of luxury apartments and hotels.

The stubbornness seems to extend to the determination of residents to hold onto their property today. "We stay here until we die," Andrade explains.

A similar resolve has come to define Brazil as a country. It survived decades of military rule and a long spell of hyperinflation in the 1980s to emerge stronger than before in the late 1990s. It now has one of the 10 largest economies in the world and is hosting the FIFA World Cup and the Summer Olympics back to back, a feat no other country has managed.

On top of that, it has positioned itself as a leader in South-South affairs in forums like the BRICS grouping that gathers the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Most recently, Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff has taken the lead in seeking to limit the United States' (US) control of the internet after revelations about spying on international communications.

Burden of the past

The relationship between Africa and Brazil, sure to be dusted off as the FIFA World Cup kicks off in June, is long and complex. Between the 16th and the 19th centuries, millions of slaves were shipped from the coast of West Africa across the Atlantic.

The akara (fried bean cake) of Nigeria's Yoruba people crossed the Atlantic to become acarajé. Certainly, colonialism features prominently in the Brazil-Africa historical narrative. Portugal's colonial adventure connects Brazil, Angola and Mozambique. It was around these historical burdens that Brazil and Africa had negotiated their relationship – an undeniable past, but no effort at a future.

Today, wealthy Angolans pile into Rio to shop and recycle petrodollars. While Lusophone young people in Africa affect a Brazilian accent, older generations stay in to watch telenovelas from the Brazilian TV network Rede Globo.

Things changed with the election of Lula as Brazil's president in 2003. He doubled the number of Brazilian embassies in Africa, a gesture reciprocated by African countries, and visited the continent 12 times – a record for any Brazilian head of state. He also increased financial and technical aid.

"Lula turned [Brazil's] gaze south, to Africa," says Celso Marcondes, coordinator of the Africa initiative at the Instituto Lula think tank. It helped that many African countries were at that point finally leaving behind an era defined by dictators, wars and stunted growth.

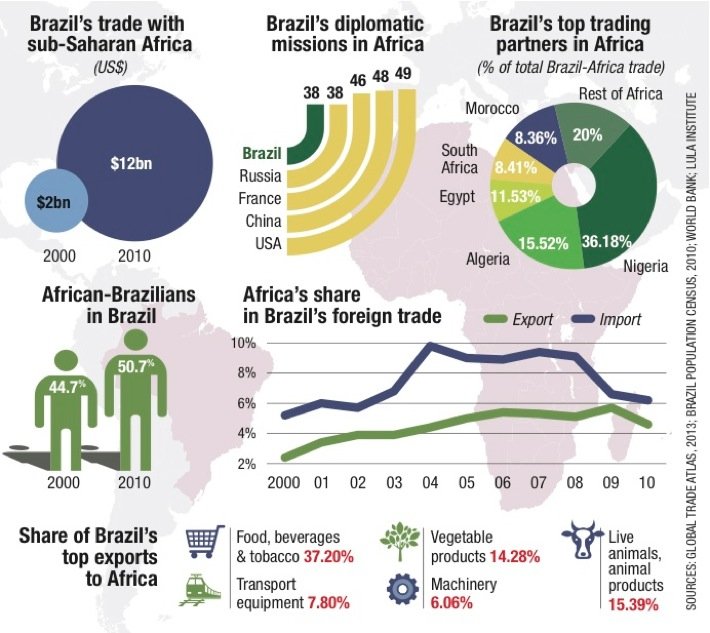

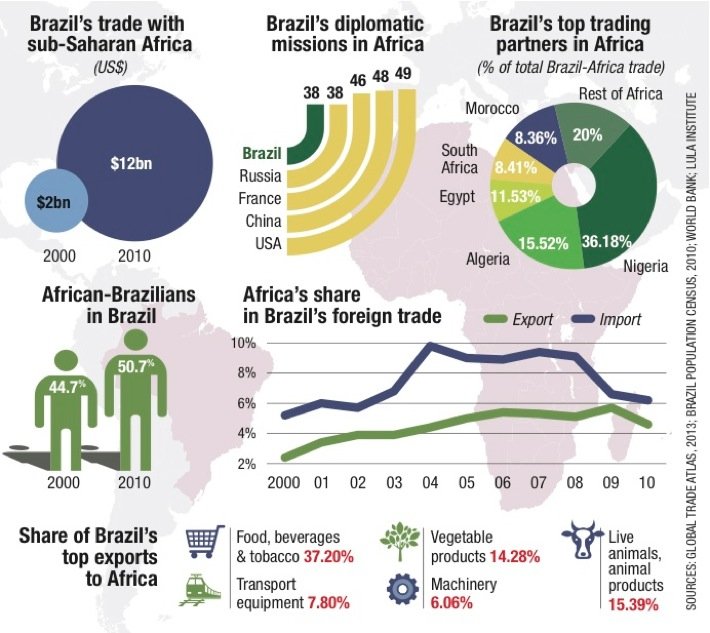

But in business, sentimental and historical ties count for little. Under Lula, trade between Brazil and Africa grew fivefold to $27bn between 2002 and 2012. Minerals accounted for 84% of Brazil's $14.3bn in imports from Africa in 2012.

Brazil's appetite for Africa's natural resources – mainly oil and gas – account for its consistently negative trade balance with the continent. In return, it exports food products, biofuels and manufactured goods.

Even though Brazil has found it easier to do business in former Portuguese colonies for linguistic reasons, its sphere of engagement extends further than that. Its largest trade partners in Africa are Nigeria, Algeria, South Africa and Egypt. Those four account for more than half of the volume of trade.

Buckling inflation

This hard-nosed, economically confident Brazil that Lula was elected to lead was one poised for emergence as a global power. Credit for this should go to his predecessor, Fernando Cardoso, under whom – first as finance minister (1993-1994) and then as president (1995- 2003) – Brazil broke the grip of inflation.

Conquering inflation paved the way for economic transformation. Purchasing power improved, and Brazil was already familiar with the business of conquering poverty when Lula took over.

If the slaying of hyperinflation in 1994 was the country's economic watershed, the political one happened in 1988: the launch of a new constitution after almost three decades of military rule. That "social democratic" constitution allowed Brazil to "[settle] scores with the past," says Sérgio Fausto, executive director of the Fundação Instituto Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

Embedded in the new constitution was the idea of a state that liberally devoted its resources to social welfare.

The Brazilian government has also embraced the idea of the state play- ing a strong role in the economy. Like China, South Korea and Japan before it, Brazil used a combination of trade barriers and industrial support for sectors it considered critical for economic development.

This particular policy mix is now a live debate in Africa. There are many lessons that African governments could learn from Brazil, especially in terms of infrastructure development, techno- logical innovation and social welfare.

Water and jobs

In Brazil's semi-arid north-eastern region – home to a third of the country's population – a government partnership with development organisations has brought 700,000 water cisterns to the smallholder farmers. The cisterns provide access to water for crops and farm animals, mitigating the devastating impact of droughts. The cisterns are useful in more than one way – apart from their direct impact on the availability of water, constructing them provides jobs.

Non-governmental organisation worker Carlos Magno de Medeiros Morais says the cistern project, which has consumed R$1bn ($450m) in government funding, is "one of the most successful programmes in this region. It's cheap, easy to build and owned by the farmers."

Farmer Joelma Pereira is one of the beneficiaries of the project. She started her farm on a half-hectare plot she bought in 2001. Today she owns 7ha that grow corn, beans and fruit. Before the cisterns, her family had to trek long distances in search of water. "Now we don't have to do that any more. We can use the time more productively," Pereira says. Small farms like hers produce 80% of all the food consumed in Brazil.

Nigeria's north-east faces similar water shortages. Analysts link the impact of this – on agricultural yields and poverty levels – to the heightened levels of unrest that have plagued the region in recent decades and which has culminated in the emergence of Al Qaeda-affiliated terrorist group Boko Haram.

Arguably Brazil's most ambitious and successful home-grown project is Bolsa Família (Family Purse). Lula launched it in 2003 to provide conditional cash grants – amounting to an average of $100 per family per month – to the country's poorest families.

The programme aims to boost incomes just past the poverty level of $1.25 per person per day. The money, paid into bank accounts associated with the programme, is targeted at women. "The state tends to believe that women are more reliable than men, that they allocate family money better," says Fausto.

The government spent $12bn on Bolsa Família in 2013, covering 14.1 million families. Social development minister Tereza Campello says every R$1 invested in Bolsa Família delivers R$1.78 in returns to the country's gross domestic product.

Going further

Amid concerns that extreme poverty still persists, President Rousseff launched the Brasil Sem Miséria ('Brazil Without Poverty') programme, which seeks to expand Bolsa Família's reach. The number of Brazilians living below the poverty line of $2 per day nearly halved from 21% of the population in 2003 to 11% in 2009 according to the World Bank.

Nonetheless, many Brazilians still see themselves as being a long way from the promised land, suggesting that Africans should be wary of making any rigid comparisons. Discontent has mounted in the face of difficult conditions. An ageing population, rising inflation, currency devaluation and slowing economic growth have placed the country on a tight economic rope.

Public anger heightened as the World Cup drew closer. Brazil planned to spend about $15bn to host the 2014 tournament. Many citizens say that money should be spent on upgrading schools, hospitals and roads. "This is not the time for Brazil to host the World Cup," argues a São Paulo taxi driver, "the stadiums cost too much."

Activist and teacher Michelle Carvalho is a Bolsa Família sceptic. She points out that while it helps ensure that school at- tendance rates are high, it does nothing for the quality of teaching. "It's an entitlement mentality, not a mentality for trans- forming yourself," she says, adding that the problem is passed down generations.

Poverty is racial

But minister Campello has data challenging this criticism of Bolsa Família. She says that 75% of adult members of beneficiary families are employed, a pro- portion similar to that for the segment of the population that does not participate in Bolsa Família.

Inequality is a challenge all countries face. But in Brazil it is especially acute, says Alexandre Chiavegatto, a professor at São Paulo university: "The poorest Brazilians are among the poorest people in the world. The richest Brazilians are almost as rich as the richest Americans."

Poverty is pronounced along racial lines. According to government data, three of every four Bolsa Família beneficiary families are black. South Africa has even greater inequality and is divided by debates over policy, especially black economic empowerment.

The Brazilian government has concerns at the strategic level, too. Writing in the London Review of Books in 2011, professor Perry Anderson picked apart the supposed inevitability of Brazil's economic emergence in the 2000s. He points to the demand for raw materials from China, in particular soy and iron ore, and the cheap credit generated by the US Federal Reserve in an effort to stop a financial bubble bursting. Both of these external forces turbo-charged Brazil's growth.

But – and here South Africa may again feel a pang of recognition – Chinese resource demand also came with a torrent of cheap goods that damaged sections of Brazil's manufacturing sector. While the going was easy, the impetus to reform manufacturing by, for example, reforming the skills base, was not there.

Now that China's economy is cooling rapidly, global commodity demand is abating and the era of cheap money over, Brazil is developing an almighty headache. Can Africa learn from Brazil's failures, as well as its triumphs?

Brasília Teimosa, an oceanfront settlement in the north-eastern city of Recife, is gentrifying. Rents are rising, and homes are taking on new floors and replacing their weather-beaten facades with gleaming ceramic tiles studded with aluminium doors and windows. Hotel porter Romualdo Andrade, 45, points out a series of steel street lights being installed to replace the concrete ones. They are more resistant to the salt-strewn breeze from the shark-infested ocean, he explains. "The only thing that resists the salt breeze is ugly girls," Andrade says, laughing.

He traces the turning point to about a decade ago, when President Luiz Inácio 'Lula' da Silva spearheaded a four-part regeneration project that involved pulling down the least habitable of the settlement's structures – while paying the occupants a monthly allowance to enable them to rent proper housing – and building a sea wall, roads and parks.

About five decades ago, Brasília Teimosa was a proper slum full of houses on stilts that rose out of the swamp. The Teimosa in its name means stubborn, Andrade says – a testament to the resistance its earliest inhabitants put up in the face of government attempts to demolish the slum and pave way for the reassignment of the prized land to developers of luxury apartments and hotels.

The stubbornness seems to extend to the determination of residents to hold onto their property today. "We stay here until we die," Andrade explains.

A similar resolve has come to define Brazil as a country. It survived decades of military rule and a long spell of hyperinflation in the 1980s to emerge stronger than before in the late 1990s. It now has one of the 10 largest economies in the world and is hosting the FIFA World Cup and the Summer Olympics back to back, a feat no other country has managed.

On top of that, it has positioned itself as a leader in South-South affairs in forums like the BRICS grouping that gathers the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Most recently, Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff has taken the lead in seeking to limit the United States' (US) control of the internet after revelations about spying on international communications.

Burden of the past

The relationship between Africa and Brazil, sure to be dusted off as the FIFA World Cup kicks off in June, is long and complex. Between the 16th and the 19th centuries, millions of slaves were shipped from the coast of West Africa across the Atlantic.

The akara (fried bean cake) of Nigeria's Yoruba people crossed the Atlantic to become acarajé. Certainly, colonialism features prominently in the Brazil-Africa historical narrative. Portugal's colonial adventure connects Brazil, Angola and Mozambique. It was around these historical burdens that Brazil and Africa had negotiated their relationship – an undeniable past, but no effort at a future.

Today, wealthy Angolans pile into Rio to shop and recycle petrodollars. While Lusophone young people in Africa affect a Brazilian accent, older generations stay in to watch telenovelas from the Brazilian TV network Rede Globo.

Things changed with the election of Lula as Brazil's president in 2003. He doubled the number of Brazilian embassies in Africa, a gesture reciprocated by African countries, and visited the continent 12 times – a record for any Brazilian head of state. He also increased financial and technical aid.

"Lula turned [Brazil's] gaze south, to Africa," says Celso Marcondes, coordinator of the Africa initiative at the Instituto Lula think tank. It helped that many African countries were at that point finally leaving behind an era defined by dictators, wars and stunted growth.

But in business, sentimental and historical ties count for little. Under Lula, trade between Brazil and Africa grew fivefold to $27bn between 2002 and 2012. Minerals accounted for 84% of Brazil's $14.3bn in imports from Africa in 2012.

Brazil's appetite for Africa's natural resources – mainly oil and gas – account for its consistently negative trade balance with the continent. In return, it exports food products, biofuels and manufactured goods.

Even though Brazil has found it easier to do business in former Portuguese colonies for linguistic reasons, its sphere of engagement extends further than that. Its largest trade partners in Africa are Nigeria, Algeria, South Africa and Egypt. Those four account for more than half of the volume of trade.

Buckling inflation

This hard-nosed, economically confident Brazil that Lula was elected to lead was one poised for emergence as a global power. Credit for this should go to his predecessor, Fernando Cardoso, under whom – first as finance minister (1993-1994) and then as president (1995- 2003) – Brazil broke the grip of inflation.

Conquering inflation paved the way for economic transformation. Purchasing power improved, and Brazil was already familiar with the business of conquering poverty when Lula took over.

If the slaying of hyperinflation in 1994 was the country's economic watershed, the political one happened in 1988: the launch of a new constitution after almost three decades of military rule. That "social democratic" constitution allowed Brazil to "[settle] scores with the past," says Sérgio Fausto, executive director of the Fundação Instituto Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

Embedded in the new constitution was the idea of a state that liberally devoted its resources to social welfare.

The Brazilian government has also embraced the idea of the state play- ing a strong role in the economy. Like China, South Korea and Japan before it, Brazil used a combination of trade barriers and industrial support for sectors it considered critical for economic development.

This particular policy mix is now a live debate in Africa. There are many lessons that African governments could learn from Brazil, especially in terms of infrastructure development, techno- logical innovation and social welfare.

Water and jobs

In Brazil's semi-arid north-eastern region – home to a third of the country's population – a government partnership with development organisations has brought 700,000 water cisterns to the smallholder farmers. The cisterns provide access to water for crops and farm animals, mitigating the devastating impact of droughts. The cisterns are useful in more than one way – apart from their direct impact on the availability of water, constructing them provides jobs.

Non-governmental organisation worker Carlos Magno de Medeiros Morais says the cistern project, which has consumed R$1bn ($450m) in government funding, is "one of the most successful programmes in this region. It's cheap, easy to build and owned by the farmers."

Farmer Joelma Pereira is one of the beneficiaries of the project. She started her farm on a half-hectare plot she bought in 2001. Today she owns 7ha that grow corn, beans and fruit. Before the cisterns, her family had to trek long distances in search of water. "Now we don't have to do that any more. We can use the time more productively," Pereira says. Small farms like hers produce 80% of all the food consumed in Brazil.

Nigeria's north-east faces similar water shortages. Analysts link the impact of this – on agricultural yields and poverty levels – to the heightened levels of unrest that have plagued the region in recent decades and which has culminated in the emergence of Al Qaeda-affiliated terrorist group Boko Haram.

Arguably Brazil's most ambitious and successful home-grown project is Bolsa Família (Family Purse). Lula launched it in 2003 to provide conditional cash grants – amounting to an average of $100 per family per month – to the country's poorest families.

The programme aims to boost incomes just past the poverty level of $1.25 per person per day. The money, paid into bank accounts associated with the programme, is targeted at women. "The state tends to believe that women are more reliable than men, that they allocate family money better," says Fausto.

The government spent $12bn on Bolsa Família in 2013, covering 14.1 million families. Social development minister Tereza Campello says every R$1 invested in Bolsa Família delivers R$1.78 in returns to the country's gross domestic product.

Going further

Amid concerns that extreme poverty still persists, President Rousseff launched the Brasil Sem Miséria ('Brazil Without Poverty') programme, which seeks to expand Bolsa Família's reach. The number of Brazilians living below the poverty line of $2 per day nearly halved from 21% of the population in 2003 to 11% in 2009 according to the World Bank.

Nonetheless, many Brazilians still see themselves as being a long way from the promised land, suggesting that Africans should be wary of making any rigid comparisons. Discontent has mounted in the face of difficult conditions. An ageing population, rising inflation, currency devaluation and slowing economic growth have placed the country on a tight economic rope.

Public anger heightened as the World Cup drew closer. Brazil planned to spend about $15bn to host the 2014 tournament. Many citizens say that money should be spent on upgrading schools, hospitals and roads. "This is not the time for Brazil to host the World Cup," argues a São Paulo taxi driver, "the stadiums cost too much."

Activist and teacher Michelle Carvalho is a Bolsa Família sceptic. She points out that while it helps ensure that school at- tendance rates are high, it does nothing for the quality of teaching. "It's an entitlement mentality, not a mentality for trans- forming yourself," she says, adding that the problem is passed down generations.

Poverty is racial

But minister Campello has data challenging this criticism of Bolsa Família. She says that 75% of adult members of beneficiary families are employed, a pro- portion similar to that for the segment of the population that does not participate in Bolsa Família.

Inequality is a challenge all countries face. But in Brazil it is especially acute, says Alexandre Chiavegatto, a professor at São Paulo university: "The poorest Brazilians are among the poorest people in the world. The richest Brazilians are almost as rich as the richest Americans."

Poverty is pronounced along racial lines. According to government data, three of every four Bolsa Família beneficiary families are black. South Africa has even greater inequality and is divided by debates over policy, especially black economic empowerment.

The Brazilian government has concerns at the strategic level, too. Writing in the London Review of Books in 2011, professor Perry Anderson picked apart the supposed inevitability of Brazil's economic emergence in the 2000s. He points to the demand for raw materials from China, in particular soy and iron ore, and the cheap credit generated by the US Federal Reserve in an effort to stop a financial bubble bursting. Both of these external forces turbo-charged Brazil's growth.

But – and here South Africa may again feel a pang of recognition – Chinese resource demand also came with a torrent of cheap goods that damaged sections of Brazil's manufacturing sector. While the going was easy, the impetus to reform manufacturing by, for example, reforming the skills base, was not there.

Now that China's economy is cooling rapidly, global commodity demand is abating and the era of cheap money over, Brazil is developing an almighty headache. Can Africa learn from Brazil's failures, as well as its triumphs?

*theafricareport]]>

*theafricareport]]>

Brasília Teimosa, an oceanfront settlement in the north-eastern city of Recife, is gentrifying. Rents are rising, and homes are taking on new floors and replacing their weather-beaten facades with gleaming ceramic tiles studded with aluminium doors and windows. Hotel porter Romualdo Andrade, 45, points out a series of steel street lights being installed to replace the concrete ones. They are more resistant to the salt-strewn breeze from the shark-infested ocean, he explains. "The only thing that resists the salt breeze is ugly girls," Andrade says, laughing.

He traces the turning point to about a decade ago, when President Luiz Inácio 'Lula' da Silva spearheaded a four-part regeneration project that involved pulling down the least habitable of the settlement's structures – while paying the occupants a monthly allowance to enable them to rent proper housing – and building a sea wall, roads and parks.

About five decades ago, Brasília Teimosa was a proper slum full of houses on stilts that rose out of the swamp. The Teimosa in its name means stubborn, Andrade says – a testament to the resistance its earliest inhabitants put up in the face of government attempts to demolish the slum and pave way for the reassignment of the prized land to developers of luxury apartments and hotels.

The stubbornness seems to extend to the determination of residents to hold onto their property today. "We stay here until we die," Andrade explains.

A similar resolve has come to define Brazil as a country. It survived decades of military rule and a long spell of hyperinflation in the 1980s to emerge stronger than before in the late 1990s. It now has one of the 10 largest economies in the world and is hosting the FIFA World Cup and the Summer Olympics back to back, a feat no other country has managed.

On top of that, it has positioned itself as a leader in South-South affairs in forums like the BRICS grouping that gathers the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Most recently, Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff has taken the lead in seeking to limit the United States' (US) control of the internet after revelations about spying on international communications.

Burden of the past

The relationship between Africa and Brazil, sure to be dusted off as the FIFA World Cup kicks off in June, is long and complex. Between the 16th and the 19th centuries, millions of slaves were shipped from the coast of West Africa across the Atlantic.

The akara (fried bean cake) of Nigeria's Yoruba people crossed the Atlantic to become acarajé. Certainly, colonialism features prominently in the Brazil-Africa historical narrative. Portugal's colonial adventure connects Brazil, Angola and Mozambique. It was around these historical burdens that Brazil and Africa had negotiated their relationship – an undeniable past, but no effort at a future.

Today, wealthy Angolans pile into Rio to shop and recycle petrodollars. While Lusophone young people in Africa affect a Brazilian accent, older generations stay in to watch telenovelas from the Brazilian TV network Rede Globo.

Things changed with the election of Lula as Brazil's president in 2003. He doubled the number of Brazilian embassies in Africa, a gesture reciprocated by African countries, and visited the continent 12 times – a record for any Brazilian head of state. He also increased financial and technical aid.

"Lula turned [Brazil's] gaze south, to Africa," says Celso Marcondes, coordinator of the Africa initiative at the Instituto Lula think tank. It helped that many African countries were at that point finally leaving behind an era defined by dictators, wars and stunted growth.

But in business, sentimental and historical ties count for little. Under Lula, trade between Brazil and Africa grew fivefold to $27bn between 2002 and 2012. Minerals accounted for 84% of Brazil's $14.3bn in imports from Africa in 2012.

Brazil's appetite for Africa's natural resources – mainly oil and gas – account for its consistently negative trade balance with the continent. In return, it exports food products, biofuels and manufactured goods.

Even though Brazil has found it easier to do business in former Portuguese colonies for linguistic reasons, its sphere of engagement extends further than that. Its largest trade partners in Africa are Nigeria, Algeria, South Africa and Egypt. Those four account for more than half of the volume of trade.

Buckling inflation

This hard-nosed, economically confident Brazil that Lula was elected to lead was one poised for emergence as a global power. Credit for this should go to his predecessor, Fernando Cardoso, under whom – first as finance minister (1993-1994) and then as president (1995- 2003) – Brazil broke the grip of inflation.

Conquering inflation paved the way for economic transformation. Purchasing power improved, and Brazil was already familiar with the business of conquering poverty when Lula took over.

If the slaying of hyperinflation in 1994 was the country's economic watershed, the political one happened in 1988: the launch of a new constitution after almost three decades of military rule. That "social democratic" constitution allowed Brazil to "[settle] scores with the past," says Sérgio Fausto, executive director of the Fundação Instituto Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

Embedded in the new constitution was the idea of a state that liberally devoted its resources to social welfare.

The Brazilian government has also embraced the idea of the state play- ing a strong role in the economy. Like China, South Korea and Japan before it, Brazil used a combination of trade barriers and industrial support for sectors it considered critical for economic development.

This particular policy mix is now a live debate in Africa. There are many lessons that African governments could learn from Brazil, especially in terms of infrastructure development, techno- logical innovation and social welfare.

Water and jobs

In Brazil's semi-arid north-eastern region – home to a third of the country's population – a government partnership with development organisations has brought 700,000 water cisterns to the smallholder farmers. The cisterns provide access to water for crops and farm animals, mitigating the devastating impact of droughts. The cisterns are useful in more than one way – apart from their direct impact on the availability of water, constructing them provides jobs.

Non-governmental organisation worker Carlos Magno de Medeiros Morais says the cistern project, which has consumed R$1bn ($450m) in government funding, is "one of the most successful programmes in this region. It's cheap, easy to build and owned by the farmers."

Farmer Joelma Pereira is one of the beneficiaries of the project. She started her farm on a half-hectare plot she bought in 2001. Today she owns 7ha that grow corn, beans and fruit. Before the cisterns, her family had to trek long distances in search of water. "Now we don't have to do that any more. We can use the time more productively," Pereira says. Small farms like hers produce 80% of all the food consumed in Brazil.

Nigeria's north-east faces similar water shortages. Analysts link the impact of this – on agricultural yields and poverty levels – to the heightened levels of unrest that have plagued the region in recent decades and which has culminated in the emergence of Al Qaeda-affiliated terrorist group Boko Haram.

Arguably Brazil's most ambitious and successful home-grown project is Bolsa Família (Family Purse). Lula launched it in 2003 to provide conditional cash grants – amounting to an average of $100 per family per month – to the country's poorest families.

The programme aims to boost incomes just past the poverty level of $1.25 per person per day. The money, paid into bank accounts associated with the programme, is targeted at women. "The state tends to believe that women are more reliable than men, that they allocate family money better," says Fausto.

The government spent $12bn on Bolsa Família in 2013, covering 14.1 million families. Social development minister Tereza Campello says every R$1 invested in Bolsa Família delivers R$1.78 in returns to the country's gross domestic product.

Going further

Amid concerns that extreme poverty still persists, President Rousseff launched the Brasil Sem Miséria ('Brazil Without Poverty') programme, which seeks to expand Bolsa Família's reach. The number of Brazilians living below the poverty line of $2 per day nearly halved from 21% of the population in 2003 to 11% in 2009 according to the World Bank.

Nonetheless, many Brazilians still see themselves as being a long way from the promised land, suggesting that Africans should be wary of making any rigid comparisons. Discontent has mounted in the face of difficult conditions. An ageing population, rising inflation, currency devaluation and slowing economic growth have placed the country on a tight economic rope.

Public anger heightened as the World Cup drew closer. Brazil planned to spend about $15bn to host the 2014 tournament. Many citizens say that money should be spent on upgrading schools, hospitals and roads. "This is not the time for Brazil to host the World Cup," argues a São Paulo taxi driver, "the stadiums cost too much."

Activist and teacher Michelle Carvalho is a Bolsa Família sceptic. She points out that while it helps ensure that school at- tendance rates are high, it does nothing for the quality of teaching. "It's an entitlement mentality, not a mentality for trans- forming yourself," she says, adding that the problem is passed down generations.

Poverty is racial

But minister Campello has data challenging this criticism of Bolsa Família. She says that 75% of adult members of beneficiary families are employed, a pro- portion similar to that for the segment of the population that does not participate in Bolsa Família.

Inequality is a challenge all countries face. But in Brazil it is especially acute, says Alexandre Chiavegatto, a professor at São Paulo university: "The poorest Brazilians are among the poorest people in the world. The richest Brazilians are almost as rich as the richest Americans."

Poverty is pronounced along racial lines. According to government data, three of every four Bolsa Família beneficiary families are black. South Africa has even greater inequality and is divided by debates over policy, especially black economic empowerment.

The Brazilian government has concerns at the strategic level, too. Writing in the London Review of Books in 2011, professor Perry Anderson picked apart the supposed inevitability of Brazil's economic emergence in the 2000s. He points to the demand for raw materials from China, in particular soy and iron ore, and the cheap credit generated by the US Federal Reserve in an effort to stop a financial bubble bursting. Both of these external forces turbo-charged Brazil's growth.

But – and here South Africa may again feel a pang of recognition – Chinese resource demand also came with a torrent of cheap goods that damaged sections of Brazil's manufacturing sector. While the going was easy, the impetus to reform manufacturing by, for example, reforming the skills base, was not there.

Now that China's economy is cooling rapidly, global commodity demand is abating and the era of cheap money over, Brazil is developing an almighty headache. Can Africa learn from Brazil's failures, as well as its triumphs?

Brasília Teimosa, an oceanfront settlement in the north-eastern city of Recife, is gentrifying. Rents are rising, and homes are taking on new floors and replacing their weather-beaten facades with gleaming ceramic tiles studded with aluminium doors and windows. Hotel porter Romualdo Andrade, 45, points out a series of steel street lights being installed to replace the concrete ones. They are more resistant to the salt-strewn breeze from the shark-infested ocean, he explains. "The only thing that resists the salt breeze is ugly girls," Andrade says, laughing.

He traces the turning point to about a decade ago, when President Luiz Inácio 'Lula' da Silva spearheaded a four-part regeneration project that involved pulling down the least habitable of the settlement's structures – while paying the occupants a monthly allowance to enable them to rent proper housing – and building a sea wall, roads and parks.

About five decades ago, Brasília Teimosa was a proper slum full of houses on stilts that rose out of the swamp. The Teimosa in its name means stubborn, Andrade says – a testament to the resistance its earliest inhabitants put up in the face of government attempts to demolish the slum and pave way for the reassignment of the prized land to developers of luxury apartments and hotels.

The stubbornness seems to extend to the determination of residents to hold onto their property today. "We stay here until we die," Andrade explains.

A similar resolve has come to define Brazil as a country. It survived decades of military rule and a long spell of hyperinflation in the 1980s to emerge stronger than before in the late 1990s. It now has one of the 10 largest economies in the world and is hosting the FIFA World Cup and the Summer Olympics back to back, a feat no other country has managed.

On top of that, it has positioned itself as a leader in South-South affairs in forums like the BRICS grouping that gathers the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Most recently, Brazil's President Dilma Rousseff has taken the lead in seeking to limit the United States' (US) control of the internet after revelations about spying on international communications.

Burden of the past

The relationship between Africa and Brazil, sure to be dusted off as the FIFA World Cup kicks off in June, is long and complex. Between the 16th and the 19th centuries, millions of slaves were shipped from the coast of West Africa across the Atlantic.

The akara (fried bean cake) of Nigeria's Yoruba people crossed the Atlantic to become acarajé. Certainly, colonialism features prominently in the Brazil-Africa historical narrative. Portugal's colonial adventure connects Brazil, Angola and Mozambique. It was around these historical burdens that Brazil and Africa had negotiated their relationship – an undeniable past, but no effort at a future.

Today, wealthy Angolans pile into Rio to shop and recycle petrodollars. While Lusophone young people in Africa affect a Brazilian accent, older generations stay in to watch telenovelas from the Brazilian TV network Rede Globo.

Things changed with the election of Lula as Brazil's president in 2003. He doubled the number of Brazilian embassies in Africa, a gesture reciprocated by African countries, and visited the continent 12 times – a record for any Brazilian head of state. He also increased financial and technical aid.

"Lula turned [Brazil's] gaze south, to Africa," says Celso Marcondes, coordinator of the Africa initiative at the Instituto Lula think tank. It helped that many African countries were at that point finally leaving behind an era defined by dictators, wars and stunted growth.

But in business, sentimental and historical ties count for little. Under Lula, trade between Brazil and Africa grew fivefold to $27bn between 2002 and 2012. Minerals accounted for 84% of Brazil's $14.3bn in imports from Africa in 2012.

Brazil's appetite for Africa's natural resources – mainly oil and gas – account for its consistently negative trade balance with the continent. In return, it exports food products, biofuels and manufactured goods.

Even though Brazil has found it easier to do business in former Portuguese colonies for linguistic reasons, its sphere of engagement extends further than that. Its largest trade partners in Africa are Nigeria, Algeria, South Africa and Egypt. Those four account for more than half of the volume of trade.

Buckling inflation

This hard-nosed, economically confident Brazil that Lula was elected to lead was one poised for emergence as a global power. Credit for this should go to his predecessor, Fernando Cardoso, under whom – first as finance minister (1993-1994) and then as president (1995- 2003) – Brazil broke the grip of inflation.

Conquering inflation paved the way for economic transformation. Purchasing power improved, and Brazil was already familiar with the business of conquering poverty when Lula took over.

If the slaying of hyperinflation in 1994 was the country's economic watershed, the political one happened in 1988: the launch of a new constitution after almost three decades of military rule. That "social democratic" constitution allowed Brazil to "[settle] scores with the past," says Sérgio Fausto, executive director of the Fundação Instituto Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

Embedded in the new constitution was the idea of a state that liberally devoted its resources to social welfare.

The Brazilian government has also embraced the idea of the state play- ing a strong role in the economy. Like China, South Korea and Japan before it, Brazil used a combination of trade barriers and industrial support for sectors it considered critical for economic development.

This particular policy mix is now a live debate in Africa. There are many lessons that African governments could learn from Brazil, especially in terms of infrastructure development, techno- logical innovation and social welfare.

Water and jobs

In Brazil's semi-arid north-eastern region – home to a third of the country's population – a government partnership with development organisations has brought 700,000 water cisterns to the smallholder farmers. The cisterns provide access to water for crops and farm animals, mitigating the devastating impact of droughts. The cisterns are useful in more than one way – apart from their direct impact on the availability of water, constructing them provides jobs.

Non-governmental organisation worker Carlos Magno de Medeiros Morais says the cistern project, which has consumed R$1bn ($450m) in government funding, is "one of the most successful programmes in this region. It's cheap, easy to build and owned by the farmers."

Farmer Joelma Pereira is one of the beneficiaries of the project. She started her farm on a half-hectare plot she bought in 2001. Today she owns 7ha that grow corn, beans and fruit. Before the cisterns, her family had to trek long distances in search of water. "Now we don't have to do that any more. We can use the time more productively," Pereira says. Small farms like hers produce 80% of all the food consumed in Brazil.

Nigeria's north-east faces similar water shortages. Analysts link the impact of this – on agricultural yields and poverty levels – to the heightened levels of unrest that have plagued the region in recent decades and which has culminated in the emergence of Al Qaeda-affiliated terrorist group Boko Haram.

Arguably Brazil's most ambitious and successful home-grown project is Bolsa Família (Family Purse). Lula launched it in 2003 to provide conditional cash grants – amounting to an average of $100 per family per month – to the country's poorest families.

The programme aims to boost incomes just past the poverty level of $1.25 per person per day. The money, paid into bank accounts associated with the programme, is targeted at women. "The state tends to believe that women are more reliable than men, that they allocate family money better," says Fausto.

The government spent $12bn on Bolsa Família in 2013, covering 14.1 million families. Social development minister Tereza Campello says every R$1 invested in Bolsa Família delivers R$1.78 in returns to the country's gross domestic product.

Going further

Amid concerns that extreme poverty still persists, President Rousseff launched the Brasil Sem Miséria ('Brazil Without Poverty') programme, which seeks to expand Bolsa Família's reach. The number of Brazilians living below the poverty line of $2 per day nearly halved from 21% of the population in 2003 to 11% in 2009 according to the World Bank.

Nonetheless, many Brazilians still see themselves as being a long way from the promised land, suggesting that Africans should be wary of making any rigid comparisons. Discontent has mounted in the face of difficult conditions. An ageing population, rising inflation, currency devaluation and slowing economic growth have placed the country on a tight economic rope.

Public anger heightened as the World Cup drew closer. Brazil planned to spend about $15bn to host the 2014 tournament. Many citizens say that money should be spent on upgrading schools, hospitals and roads. "This is not the time for Brazil to host the World Cup," argues a São Paulo taxi driver, "the stadiums cost too much."

Activist and teacher Michelle Carvalho is a Bolsa Família sceptic. She points out that while it helps ensure that school at- tendance rates are high, it does nothing for the quality of teaching. "It's an entitlement mentality, not a mentality for trans- forming yourself," she says, adding that the problem is passed down generations.

Poverty is racial

But minister Campello has data challenging this criticism of Bolsa Família. She says that 75% of adult members of beneficiary families are employed, a pro- portion similar to that for the segment of the population that does not participate in Bolsa Família.

Inequality is a challenge all countries face. But in Brazil it is especially acute, says Alexandre Chiavegatto, a professor at São Paulo university: "The poorest Brazilians are among the poorest people in the world. The richest Brazilians are almost as rich as the richest Americans."

Poverty is pronounced along racial lines. According to government data, three of every four Bolsa Família beneficiary families are black. South Africa has even greater inequality and is divided by debates over policy, especially black economic empowerment.

The Brazilian government has concerns at the strategic level, too. Writing in the London Review of Books in 2011, professor Perry Anderson picked apart the supposed inevitability of Brazil's economic emergence in the 2000s. He points to the demand for raw materials from China, in particular soy and iron ore, and the cheap credit generated by the US Federal Reserve in an effort to stop a financial bubble bursting. Both of these external forces turbo-charged Brazil's growth.

But – and here South Africa may again feel a pang of recognition – Chinese resource demand also came with a torrent of cheap goods that damaged sections of Brazil's manufacturing sector. While the going was easy, the impetus to reform manufacturing by, for example, reforming the skills base, was not there.

Now that China's economy is cooling rapidly, global commodity demand is abating and the era of cheap money over, Brazil is developing an almighty headache. Can Africa learn from Brazil's failures, as well as its triumphs?