The Balancing Act of Diplomacy: How Russia Struggles to Appear on Africa’s Horizon

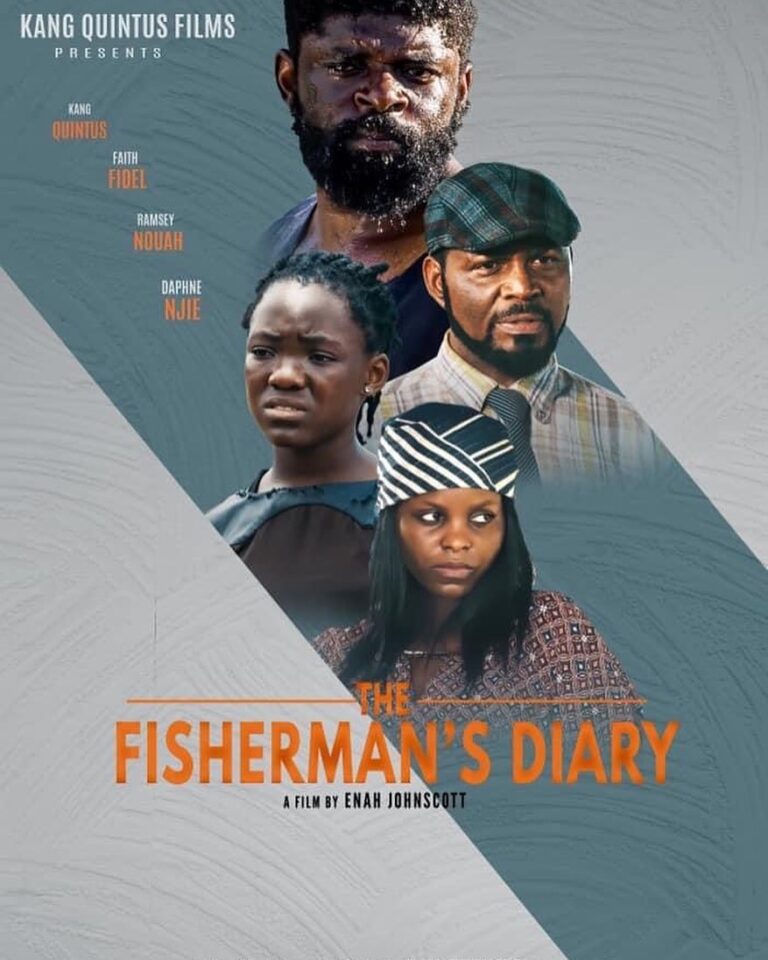

August 02, 2022By Kestér Kenn Klomegâh [caption id="attachment_99039" align="alignnone" width="768"] © Reuters/RUSSIAN FOREIGN MINISTRY

© Reuters/RUSSIAN FOREIGN MINISTRY

Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov meets Ugandan President Museveni in Entebbe[/caption] As popularly known to African leaders, Russia has thousands of decade-old undelivered pledges and several bilateral agreements signed with individual countries, yet to be implemented, in the continent. In addition, during the previous years, there has been an unprecedented huge number of “working visits” by state officials both ways, to Africa and to the Russian Federation. In an authoritative policy report presented last November titled Situation Analytical Report and prepared by 25 Russian policy experts, it was noted that Russia’s Africa policy is roughly divided into four periods, previously after the Soviet’s collapse in 1991. After the first summit held in October 2019, Russia’s relations with Africa have entered its fifth stage. According to that report, “the intensification of political contacts is only with a focus on making them demonstrative.” Russia’s foreign policy strategy regarding Africa needs to spell out and incorporate the development needs of African countries. The number of high-level meetings has increased but the share of substantive issues on the agenda remains small. There are few definitive results from such meetings. Next, there has been a lack of coordination among various state and para-state institutions working with Africa. Despite the above objective criticisms or better still the research findings, Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s trip to four African countries on 24-27 July still has considerable geopolitical significance and some implications. The four African countries on his travel agenda were Egypt, Ethiopia, Uganda and the Republic of the Congo. In a pre-departure interview with local Russian media, Lavrov shared reflections on the prospects for Russia-African relations within the context of the current geopolitical and economic changes, fearing isolation with tough sanctions after Russia’s February 24 “special military operation” in Ukraine. He unreservedly used, at least, the media platform to clarify Russia’s view of the war and attract allies outside the West, and rejected the West’s accusations that Russia is responsible for the current global economic crisis and instability. Reports said African countries are among those most affected by the ripples of the war. There are, however, other natural causes such as long seasonal droughts that complicated the situation in Africa. Lavrov reiterated an assurance that Russian grain “commitments” would be fulfilled and offered nothing more to cushion the effects of the cost-of-living crisis. In a contrast, at least, the United States offered a $1.3 billion package to help tackle hunger in Africa’s Horn. It is a historical fact that Russia’s ties with Africa declined with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The official transcripts made available after Lavrov’s meetings in Egypt offered little, much has already been said about developments in the North African and Arab world, especially those including Libya, Syria and Yemen, as well as the Palestinian-Israeli conflicts. With the geographical location of Egypt, Lavrov’s visit has tacit implications. It followed US President Joe Biden’s first visit to the Middle East, during which he visited Israel, the Palestinian territories and Saudi Arabia. Biden also took part in a summit of the six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council, in addition to Egypt, Jordan and Iraq. Lavrov’s efforts toward building non-Western ties at this crucial time are highly commendable, especially with the Arab League Secretary-General Ahmed Aboul Gheit and representatives from the organization’s 22 member states. Egypt has significant strategic and economic ties with Russia. There are two major projects namely the building of nuclear plants, the contract signed back in 2015 and the construction of an industrial zone has been on the planning table these several years. In the aftermath of the Soviet Union, Russia continues efforts in search of possible collaboration and opportunities for cooperation in the past years. For the first time in the Republic of Congo, Lavrov delivered a special message from President Vladimir Putin to the Congolese President Denis Sassou Nguesso, at his residence in Oyo, a town 400 kilometres north of the capital, Brazzaville. Kremlin records show that Sassou-Nguesso, who has been in power since 1979, last visited Moscow in May 2019 and before that in November 2012. The Congolese leader during his visit apparently asked for Russia’s greater engagement and assistance in bringing total peace and stability in Central Africa comprising the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, Cameroon and Chad. This presents a considerable interest especially its “military-technical cooperation” to further crash French domination similar to the Republic of Mali in West Africa. Interviews made by this author confirmed that Russia would send more military experts from Wagner Group to DRC through the Central African Republic. An insider at the Congo’s Foreign Affairs Ministry confirmed the special message relates to an official invitation for Congolese President Sassou-Nguesso to visit Moscow. Understanding the political developments and much talked about transition (better to describe it as hereditary succession) of the regime from President Yoweri Museveni to his son, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, unquestionably brings Lavrov to Uganda. For Museveni, drawing closer to Russia sends a critical message about the motives for relations between Uganda and Russia. With Foreign Minister of Uganda Jeje Odongo in the city of Entebbe, Lavrov in the same traditional rhetoric mentioned “the implementation of joint projects in oil refining, energy, transport infrastructure and agricultural production.” It was decided to focus on practical efforts to move the above areas of focus forward in the course of an Intergovernmental Russian-Ugandan Commission on Economic, Scientific and Technical Cooperation meeting in October. Interesting to recall that during President Vladimir Putin’s meeting on December 11, 2012, President Museveni said “Moscow is a kind of Mecca for free movements in Africa. Muslims visit Mecca as a religious ritual, while Moscow is a kind of centre that helps various liberation movements.” Later in October 2019, Museveni expressed appreciation for the Africa–Russia meeting. “It is good to say at this meeting a few areas which we could look at. Number one is defence and security. We have supported building an army by buying good Russian equipment, aircraft, tanks, and so on. We want to buy more. We have been paying cash in the past, cash, cash, cash. What I propose is that you supply and we pay. That would be some sort of supply that would make us build faster because now we pay cash like for this Sukhoi jet, we paid cash,” Museveni said during the conversation told Putin. Lavrov displays his passion for historical references. In many of his speeches during the four-nation tour, he repeatedly stressed that it’s imperative for African leaders to support its “special military operation” in Ukraine, repeated all the Soviet assistance to Africa and the perspectives for the future of Russia-African relations. But most essentially, Lavrov has to understand that little has been achieved, both the long period before and after the first Russia-Africa summit held in October 2019. In Ethiopia where the African Union headquarters is located, and representatives of African countries are based, Russia is vying to normalize an international order and frame-shape its geostrategic posture in this capital city. Whether 25 of Africa’s 54 states abstained or did not vote to condemn Russia at the UN General Assembly resolution in March, Africans are overwhelmingly pragmatic. Most of them displayed neutrality, creating the basis for accepting whatever investment and development finance from the United States, the European Union, the Asian region, Russia and China, from every other region of the world. For external players including Russia eyeing Africa, Museveni’s thought-provoking explanation of “neutrality” during the media conference re-emphasizes the best classic diplomacy of pragmatism. “We don’t believe in being enemies of somebody’s enemy,” Museveni told Lavrov. Uganda is set to assume the chairmanship of the Non-Aligned Movement, a global body created during the Cold War by countries that wanted to escape being drifted into the geopolitical and ideological rivalry between Western powers and Communists. Lavrov, however, informed about broadening African issues in the “new version of Russia’s Foreign Policy Concept against the background of the waning of the Western direction” and his will objectively increase the share of the African direction in the work of the Foreign Ministry. Relating to the next summit, scheduled for mid-2023, “a serious package of documents that will contain almost all significant agreements” is being prepared, he said. Lavrov with his Ethiopian counterpart Demeke Mekonnnen and the African Union leadership in Addis Ababa have agreed on additional documents paving the way to a more efficient dialogue in the area of defence sales and contracts. Still on Ethiopia, Russia’s state-run nuclear corporation Rosatom and Ethiopia’s Ministry of Innovation and Technology signed a roadmap on cooperation in projects to build a nuclear power plant and a nuclear research centre in the republic. In addition, other bilateral issues, including joint energy and infrastructure projects, and education were discussed. “We have good traditions in the sphere of military and technical cooperation. Today, we confirmed our readiness to implement new plans in this sphere, including taking into account the interests of our Ethiopian friends in ensuring their defensive ability,” the Russian top diplomat said. “Russia is ready to continue providing assistance to Ethiopia in training its domestic specialists in various spheres,” he added and finally explaining that Moscow was ready to develop both bilateral humanitarian and cultural contacts and cooperation in the sphere of education with Addis Ababa. According to Lavrov, Russia has had long-standing good relations with Africa since the days of the Soviet Union which pioneered movements that culminated in decolonization. It provided assistance to the national liberation movements and then to the restoration of independent states and the rise of their economies in Africa. An undeniable fact is that many external players have also had long-term relations and continue bolstering political, economic and social ties in the continent. In his Op-Ed article, Lavrov argues: “We have been rebuilding our positions for many years now. The Africans are reciprocating. They are interested in having us. It is good to see that our African friends have a similar understanding with Russia.” The point is that Moscow is desirous to widen and deepen its presence in the continent. On the other hand, the Maghreb and African countries are, in terms of reciprocity, keen to strengthen relations with Moscow, but will avoid taking sides in the Russia-Ukraine crisis. Lavrov has successfully ended his meetings and talks in Africa. Now, the basic significant issue in its current relations is still the fact that Russia has thousands of decade-old undelivered pledges and several bilateral agreements signed with individual countries in the continent, while in the previous years there has been an unprecedented huge number of “working visits” to Africa. The development of a comprehensive partnership with African countries remains among the top priorities of Russia’s foreign policy, Moscow is open to its further build-up, Lavrov said in an Op-Ed article for the African media, and originally published on the ministry’s website. Steven Gruzd, the Head of the Russia-Africa Programme at the South African Institute of International Affairs (SAIIA), told Fox News Digital. “Africa’s leaders must realize that they might be used as props in the grand geopolitical theatre being led by these big powers.” Moscow opposes a unipolar world based only on Western interests and pursues Africa to condemn sanctions imposed against Russia. He believes that this diplomatic jockeying risks casting African countries “as pawns in a grand chess game” and African countries have to steer clear of taking sides. However, many African countries are wary of losing Western aid and trade ties should they go all in with the Kremlin. “They need to be very clear about the risks and rewards of these meetings”, added Gruzd. “Most do not want to have to choose between Russia and the West and will try to maintain relationships with both sides. This is definitely a Russian move to show they are not isolated, and what better way to do it than Minister Lavrov smiling and shaking hands with African presidents and foreign ministers?” In the context of rebuilding post-Soviet relations and now attempting at creating a new model of the global order which it hopes to lead after exiting from international organizations. In order to head an emerging global order, Russia needs to be more open, and make more inroads into the civil society, rather than close (isolating) itself from “non-Western friends” during this fast-changing crucial period – in Asia, Africa and Latin America. For instance, Africa is ready as it holds huge opportunities in various sectors for reliable, genuine and committed investors. It offers a very profitable investment destination. Despite criticisms, China has built an exemplary distinctive economic power in Africa. Besides China, Africa is largely benefitting from the European Union and Western aid flows, and economic and trade ties. Russia plays very little role in Africa’s infrastructure, agriculture and industry, and makes little effort in leveraging the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Our monitoring shows that the Russian business community hardly pays attention to the significance of AfCFTA which provides a unique and valuable platform for businesses to access an integrated African market of over 1.3 billion people. Substantively, Russia brings little to the continent, especially in the economic sectors that badly need investment. Of course, Russia basks in restoring and regaining part of its Soviet-era influence, but has problems with planning and tackling its set tasks, a lack of confidence in fulfilling its policy targets. The most important aspect is how to make strategic efforts more practical, more consistent and more effective with African countries. Without these fundamental factors, it would therefore be an illusionary step to partnering with Africa. Some policy experts have classified three directions for external partners dealing with Africa: (i) active engagement, (ii) sitting on the sideline and observing, and (iii) being a passive player. From all indications, African leaders have political sympathy and most often express either support or a neutral position for Russia. But at the same time, African leaders are very pragmatic, indiscriminately dealing with external players with adequate funds to invest in different economic sectors. Africa is in a globalized world. It is, generally, beneficial for Africa as it could take whatever is offered from either East or West, North or South. In stark contrast to key global players for instance the United States, China and the European Union and many others, Russia has limitations. For Russia to regain a part of its Soviet-era influence, it has to address its own policy approach, this time shifting towards new paradigms – to implement some of the decade-old pledges and promises, and those bilateral agreements; secondly to promote development-oriented policies and how to make these strategic efforts more practical, more consistent, more effective and most admirably result-oriented with African countries. Perhaps, reviewing or revisiting the school geography, Russia is not only by far the world’s largest country, surface-wise, but arguably also by far the wealthiest in terms of natural resources. Thus, the question is – what else could be Russia’s standing blocks in building its economic power, by investing in the needed sustainable development (not humanitarian aid), in Africa?

© Reuters/RUSSIAN FOREIGN MINISTRY

© Reuters/RUSSIAN FOREIGN MINISTRY